Photography was not born with the invention of the camera. The camera obscura was already experienced by paleolithic humans - millions of years ago during the Stone Age - who occasionally saw images of animals projected through tiny holes in their tents. The phenomenon of the pinhole was documented in China as early as 1001 BC and Aristotle and Euclid made comments on it, circa 300 BC. The phenomenon is so common that it occurs quite naturally such as when a solar eclipse is projected through holes in the canopy of a tree, or an entire building is projected onto a wall through a hole in the roof as in the image below.

Gampe, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photography began with the ability to permanently fix an image onto a surface. The first attempts were made in the early decades of the 19th century, all relying on the reduction of salts of silver to metallic silver - which is black - by the exposure to light. I was initiated in this old art of fixing light onto silver in the mid-90s when I was in middle school in India.

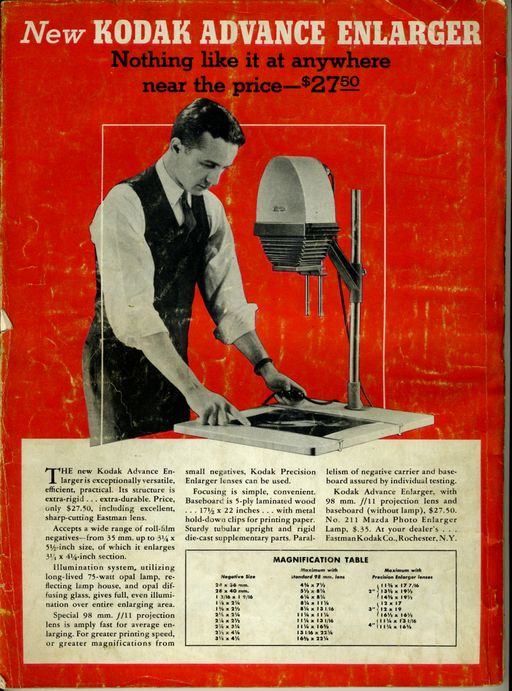

My school had built a new darkroom one summer and equipped it with various optical equipment and chemical tanks. One of my favorite things to do there was creating photograms. Photograms are more akin to drawing or painting than taking a photo with a camera. You take small ordinary objects made of glass, plastic, flowers, leaves, feathers, anything small really and place them directly on a photosensitive paper under a device called an enlarger. Light from the enlarger exposes the image onto the paper below. The variation of transparency and shadows from the objects sometimes creates delicate, almost-3D images.

Initially the paper looks blank after removing the objects from under the enlarger. It must be treated with several chemical baths to create the final picture. This is the second half of the practice of photography after the light has done its work. This task must be carried out in near total darkness save for the warm glow of a dim red lamp. In many ways this work involves far more precision and creativity than operating a camera - it's a dark art practiced in darkness.

I have a distinct memory of the sharp odor of the darkroom chemicals and how icy cold they were to the touch. Our teacher would prepare four large and shallow trays with various solutions for processing the image. The first tray contained the developer which is a chemical that turns the silver halide of the paper into a black silver powder wherever it has been exposed to light by the enlarger. If you are enlarging a film instead of creating a photogram, this process involves an inversion of the image on the film. The film in a camera turns dark wherever light falls from the camera lens. Then the silver halide paper turns dark wherever light from the enlarger falls through the brighter areas of the film; inverting the film and restoring the original scene. Hence, films are called negatives.

The image gradually fades from white onto the paper as it develops like a magic trick. A few seconds too long here and the paper could turn all black. This needs precise timing. You must carefully move the paper to the next tray containing a solution called the stop bath. Here the image stops developing further and turning all black. A quick dip in the third tray - the fixer - fixes the image permanently on paper. Finally, after a wash under cold water, the paper is left to hang from a wire, like fresh laundry.

Nesster, CC BY 2.0 DEED, via Flickr

The dark room is a relic of the past now but its legacy continues in the digital world. Menu items in editors like Photoshop such as exposure, burning and dodging, toning, and filters, all originated as physical processes in the dark room. Exposure was real time spent under the enlarger, measured precisely with a timer. Burning and dodging was achieved by carefully covering or revealing specific regions of the paper to achieve more or less exposure. The equivalent of digital filters were achieved by applying toning solutions after fixing the image, often requiring working with malodorous chemical fumes. The ammonia based Sepia toner for instance smelled like rotten eggs. Kids these days will never know!

Before every lab our class would take turns to walk about in the school gardens with a manual film camera and take photos for processing in the darkroom. It was a refreshing break in the middle of routine classwork. After our brief but invigorating photo session under the bright afternoon sun we would come indoors to the cold red darkroom. The work there stands out vividly in my memory as one of the most exciting things I learned in school, except perhaps at the computer lab. It just appealed to a latent hacker sensibility in me. Sadly, I never had the chance to step into a darkroom again after leaving high school.

The entire business of the darkroom now exists as algorithms in software. All photographic apparatus, save for the rudimentary pinhole and glass, is reduced to information processing. The smartphone camera and the photo editor are an incredible improvement over the darkroom in every way imaginable. Even in the days of film - especially color - most people would send their negatives to a lab for printing.

I'm not nostalgic for old things and while I have fond memories of the darkroom I don't miss it. The only thing that we may have lost there is the intensely tactile and visceral nature of the process. It was remarkable as a learning activity for appreciating the concepts of photo processing in a deeply tangible manner. Today, the convenience of having a camera with a free photo lab in our pockets at all times surpasses any advantages the old darkroom had. Photography is vastly more popular today than it ever was (roughly 5 billion photos taken per day). In a way so is the darkroom, abstracted into photo editing software for pros, and smartphone filters for everyone else. Tap and select Sepia, and farewell to rotten eggs!